Carrying Bones, Doing History, and Gathering with Ancestors

Convocation Address at New Brunswick Theological Seminary, Fall 2025

This past week, I delivered the convocation address at New Brunswick Theological Seminary. I was selected on account of being granted tenure and promotion at the L Russell Feakes Associate Professor of the History of Global Christianity. It is an honor I do not take lightly in an academic profession where the institution of tenure is being gutted by increasingly bloated bureaucracies in higher education and a race to the bottom for quick degrees and dwindling pools of prospective students. I also am grateful because, more importantly, the academic freedom that tenure is supposed to foster is under dire threat by the Trump administration and an anti-history agenda among the MAGA movement (which merits some more discussion in a future post).

Here, for my readers at Tables, I’m excited to share the text of my address, which begins with some thoughts on the importance of ancestors and memory in the ancient Hebrew scriptural tradition. I go from there to discuss my public history work of the past two years, working on the reburial of human remains that belonged to enslaved African American residents of Pequannock, New Jersey. Finally, I address the institutional history of New Brunswick Theological Seminary as a beneficiary of the overlap between the institution of slavery and the institutions of the Christian church in the colonial period and the early United States. We close with a Libation Ceremony honoring and listing the names of just some of those whose enslaved labor was without their consent the seed of the endowment of the seminary.

It was a powerful event, inspired by and led alongside dear colleagues in the work of African American public history. I was also delighted to have the support of colleagues, former students, my parents who flew in for the event, my spouse and children. It was also a gift that my dear brother, who has taught me much about Libation in the Yoruba tradition, Dr. Oludare Odumosu, was also present for this address and ceremony.

You can watch the recording here. It begins with colleagues Rev. Dr. Faye Tayor and Jeanette Carrillo reading scripture, as the text from Genesis 49 and 50 leads into the opening of my address.

The full text of the address is as follows:

An Opening Convocation is an occasion that gathers us. We gather at the start of a new semester, a new academic year, maybe even for some of you, a new phase of life and calling. We gather as an institution of theological higher education to think with greater rigor about our faith traditions, assembling tools to serve and equip our churches and communities for the work of justice in the face of present struggles.

So, it’s a bit odd that I’ve chosen a scripture text where Jacob being “gathered to his people” means he died. And this story, the deaths of Jacob and Joseph is the final text in Genesis and a final chapter in the story of the ancestors of the ancient Hebrew people.

Not only is it an unusual passage for such an event, the format of a convocation address may be different than the formula you get in church. I’m not gonna try to journey all the way to Calvary and close on Easter Sunday morning. That’s cuz we can do this in seminary – sit with a text in its context. We can recognize that not all our sacred texts and proclamations end in resurrection. Sometimes we need to kneel at the graveside or sit at the tombs of the ancestors. So that’s where we are going today, if you can journey with me for a few minutes. We’ll think with this scripture, I’ll discuss some of the public history work I’ve been engaged in to rebury and honor African American ancestors in New Jersey, and finally, we’ll foster a fuller historical context for our institution committed to think critically, act justly, and lead faithfully.

“Carry Up My Bones” - The Genesis Story of Ancestors

So, first, what’s going on in this scripture? Quite a lot, actually, it names the ancestors, pays critical attention to different geographies, cultures, and deathways, and presents two ancestors’s shared request: “Carry up my bones.” Ensure that I am “gathered to my ancestors.”

This story of Jacob and Joseph on their deathbeds closes the long tale of a very dysfunctional family. I put up a map of the Afro-Asiatic world of the Middle Bronze Age so you can get your bearings of where we are geographically, but you all know how the story goes:

A dreamer named Joseph is born to a deceiver named Jacob, aka Israel. Joe gets a fly coat cuz he’s daddy’s favorite, so his 11 brothers beat him, and sell to merchants. He’s enslaved and taken to Egypt, but rises to become Pharaoh’s right-hand man and facilitates Egyptian dominance in agricultural storage. Then a famine throughout the region leads his own brothers to knock on Joseph’s door to buy African grains for their survival. After some trickery and a big reveal, he reconciles and brings the whole family down to the Egyptian plain. In the final text, though, first an aged Jacob and then an aged Joseph both express a desire to be buried with their ancestors.

Here we encounter two different deathways. Abraham’s people, originally from Chaldea and then as migrants to Canaan buried their people in caves. The body would be very quickly wrapped, with some precious oils perhaps, but nothing to delay the body’s decay. You’ll recall the need for a quick burial for Jesus in the gospel accounts, so quick that they had to use a borrowed tomb. In this ancient Hebrew burial custom, the body was placed in a cave or shelf in a cave. This is like what you’d see in the mountains of Haiti, or the lowlands of New Orleans, where either rocky terrain or a high water table makes underground burial impractical. Then, after decomposition, the bones would be gathered into an ossuary, a bone box, literally gathering together all the bones of many generations into one ancestral location.

Jacob was clear on his intentions; here on his deathbed, he even made his sons take an oath. When I die, “carry up my bones” back to that cave my grandfather bought—where he and grandma, dad and mom, and my dad’s other wife who was also my aunt- my mother-aunt, were all buried—yeah, bring me back there. These weren’t our ancestral lands, but it’s where we met the living God, felt called to settle, and lived out our dysfunctional family life. Promise me. Carry up my bones. Jacob and eventually Joseph would both insist they honor the family deathways and join those ancestors.

But a second cultural context for practices of death and dying appears in this text, too. They’re in Egypt, on the plain of Goshen not far from the Great Pyramids. And Joseph is a baller in the royal court, with his own physicians—Africans who were the leading medical practitioners of the world, at this point in history. So, Joseph commands his physicians to do the Egyptian rites of removing key organs, embalming, and mummification. This is not a quick burial according to Hebrew rites. These customs and power structures of the land in which he died delayed the return of Joseph’s bones. 40 days of embalming. 70 days of mourning. Then travel. Going, going, back to back to Canaan with all of Pharaoh’s staff and the whole extended family going in a great caravan through the desert, then 7 more days of mourning. The text says that the scene was so momentous that Canaanite people named their campsite “the place of Egyptian mourning.” Jacob’s body was treated in both the manner of the powerful Egyptians and in the deathway of his nomadic family, placed in a cave in Canaan bought from the indigenous Hittites.

Joseph made his kids promise the same. Of course after the death of Joseph, the fortunes of the people dramatically shifted, growing in number but being enslaved by a new ruling dynasty. So, in the case of Joseph’s body, we hear about them throughout the following books of the Torah all the way to Joshua and Judges. His bones were delayed for centuries, in getting back home. Multiple generations carried his embalmed remains. Those bones were loaded up even as the people fled their oppressors, carted through the Red Sea, lugged through 40 years of wilderness wanderings, over mountains, through deserts, and across the Jordan River, until Joseph, too, was gathered to his ancestors.

Jacob and Joseph requested to be honored in the spaces where they and their ancestors had lived. They asked their children and descendants to remember them in culturally-relevant ways that cast their memory in a broader history of family and community. This text accounts for the dynamism of life in the ancient Afro-Asiatic world, where bodies in life and death would be treated according to different funerary practices, where people faced natural disasters, and how nomadic monotheistic people would be subject to power structures and in some cases enslaved. Even so, these people who professed faith in a living God asked that the living who come behind them not forget about their bones, keep their history, and honor their memory as essential to understanding a collective story of God’s faithfulness.

African American Ancestors in Pequannock and the Work of Public History

This story of those who took an oath to carry up the bones of their ancestors has been on my mind a lot over the past two years. At the conclusion of the Luce Foundation funded Shelter Project that I directed with Rutgers colleagues Kristin O’Brassill-Kulfan and Colin Jager, Kristin and I had some time reflecting on a shared conviction that we as historians had more to do in seeking justice for those whose bodies and cultural artifacts are held at NBTS and Rutgers.

The biblical passage’s reference to dispossessed bones and Egyptian embalming is actually most directly applicable to the Egyptian human remains that NBTS owns. Yes, NBTS claims ownership of Iset-Ha, a Ptolemaic Egyptian Priestess whose mummified body is loaned indefinitely to the Rutgers Geology museum. I have to name this injustice, but her case needs a lot more work and is an address for another time.

It was the matter of another set of human remains held by Rutgers that set off a massive public history effort I’ve been involved in for the past two years.

This began when a Rutgers task force came across human remains that had been kept in storage cabinets for about ninety years. Since at least 2022, Kristin, and Carol McCarty of the Geology Museum became champions for the cause of these bone fragments, belonging to four people, believed to be enslaved or formerly-enslaved African Americans who lived in the early nineteenth century. I was excited to join this effort in the Fall of 2023, write grants to expand its scope, and leverage the ties of the seminary by working to identify community leaders and convene an advisory council who made recommendations on how to rebury these remains.

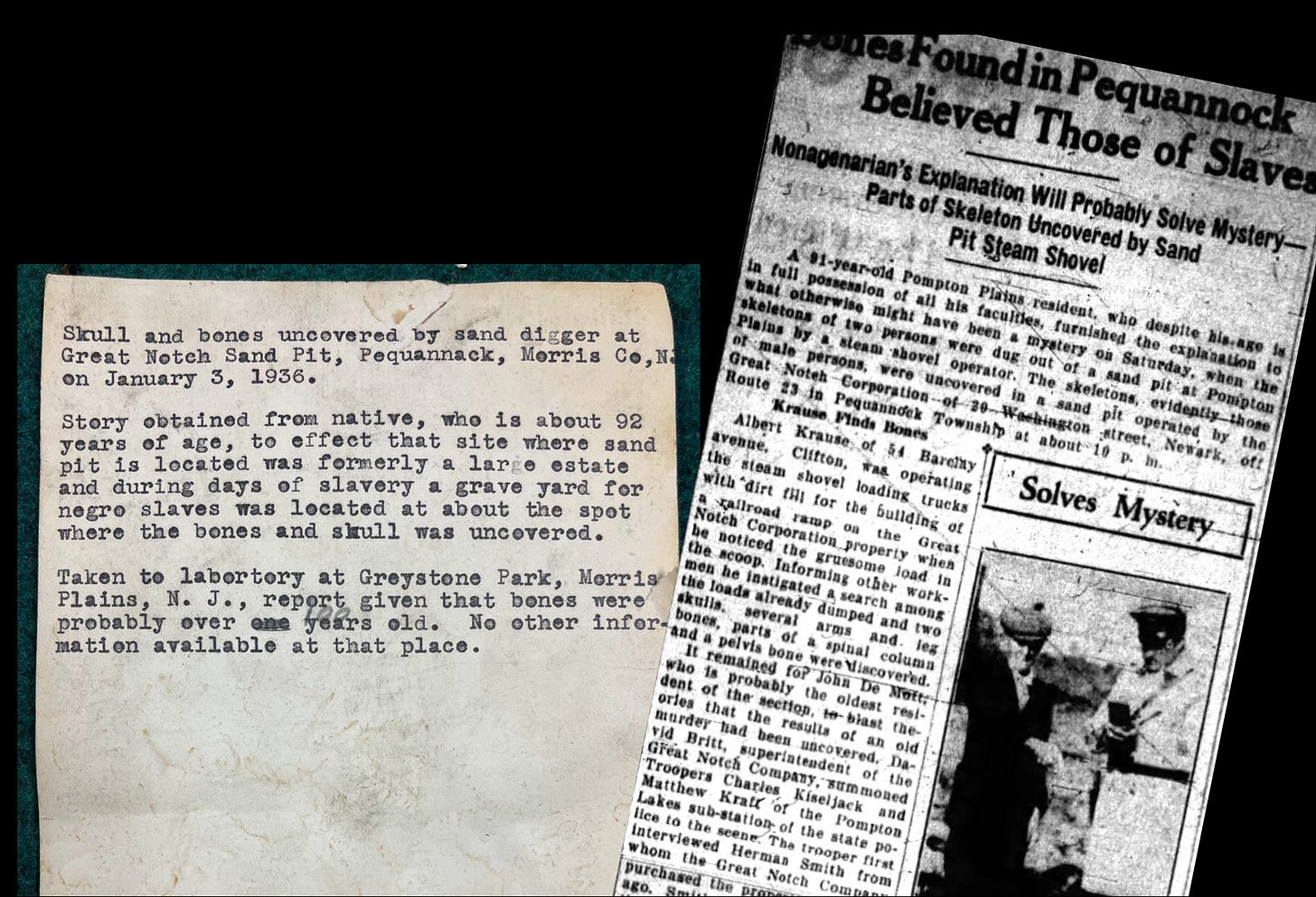

The human remains had been accidentally dug up in Pequannock in 1936 and were brought to the university in New Brunswick shortly thereafter. Local residents at the time of disinterment testified that the disturbed lands were where the DeMott family, prominent in the community and the local Reformed church, had buried the people they enslaved. These findings were substantially corroborated through records establishing evidence for the ownership of the land, and archival research in deeds, wills, censuses, birth, death, and marriage, and baptismal records identified a number of possible African American individuals.

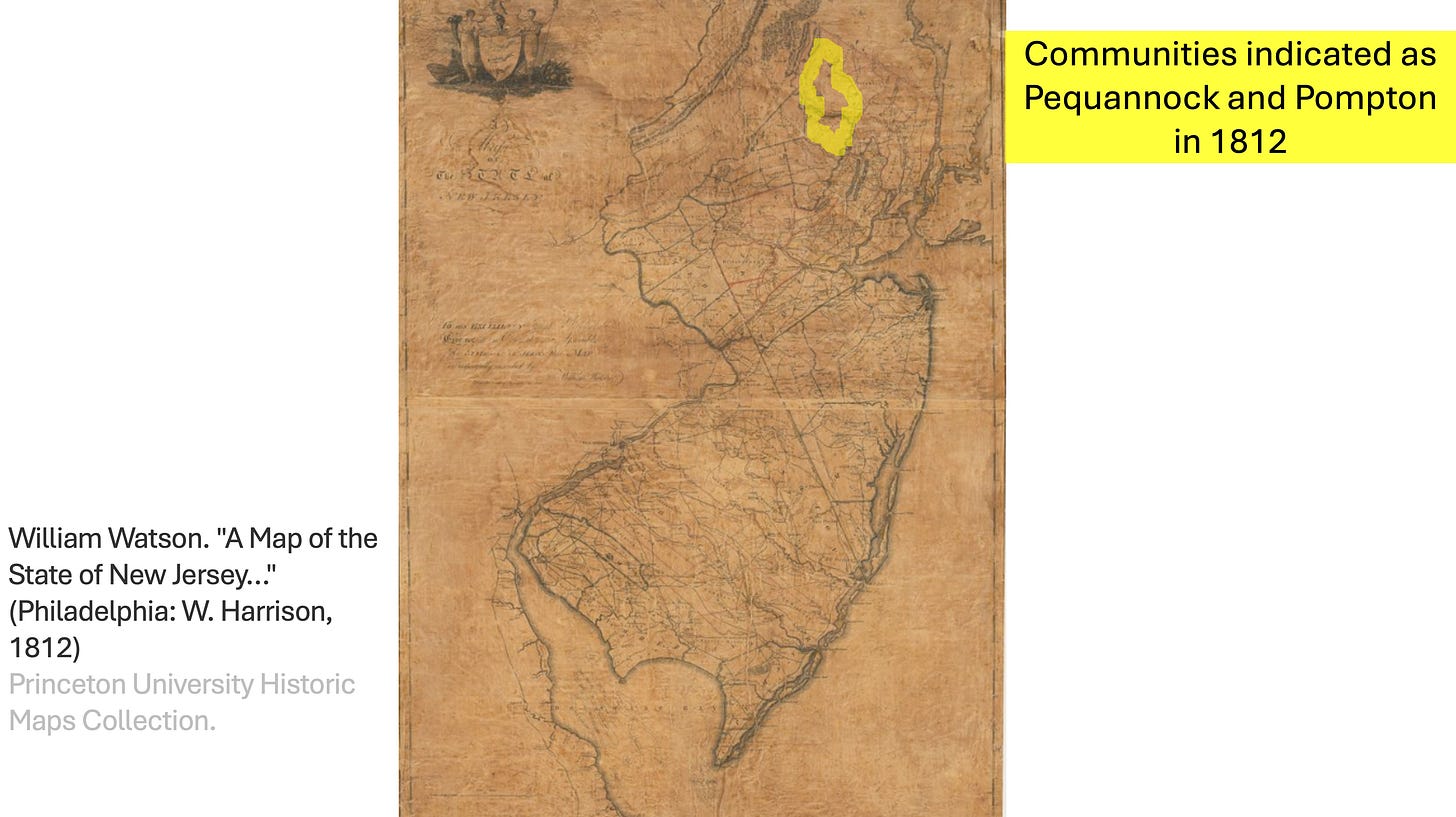

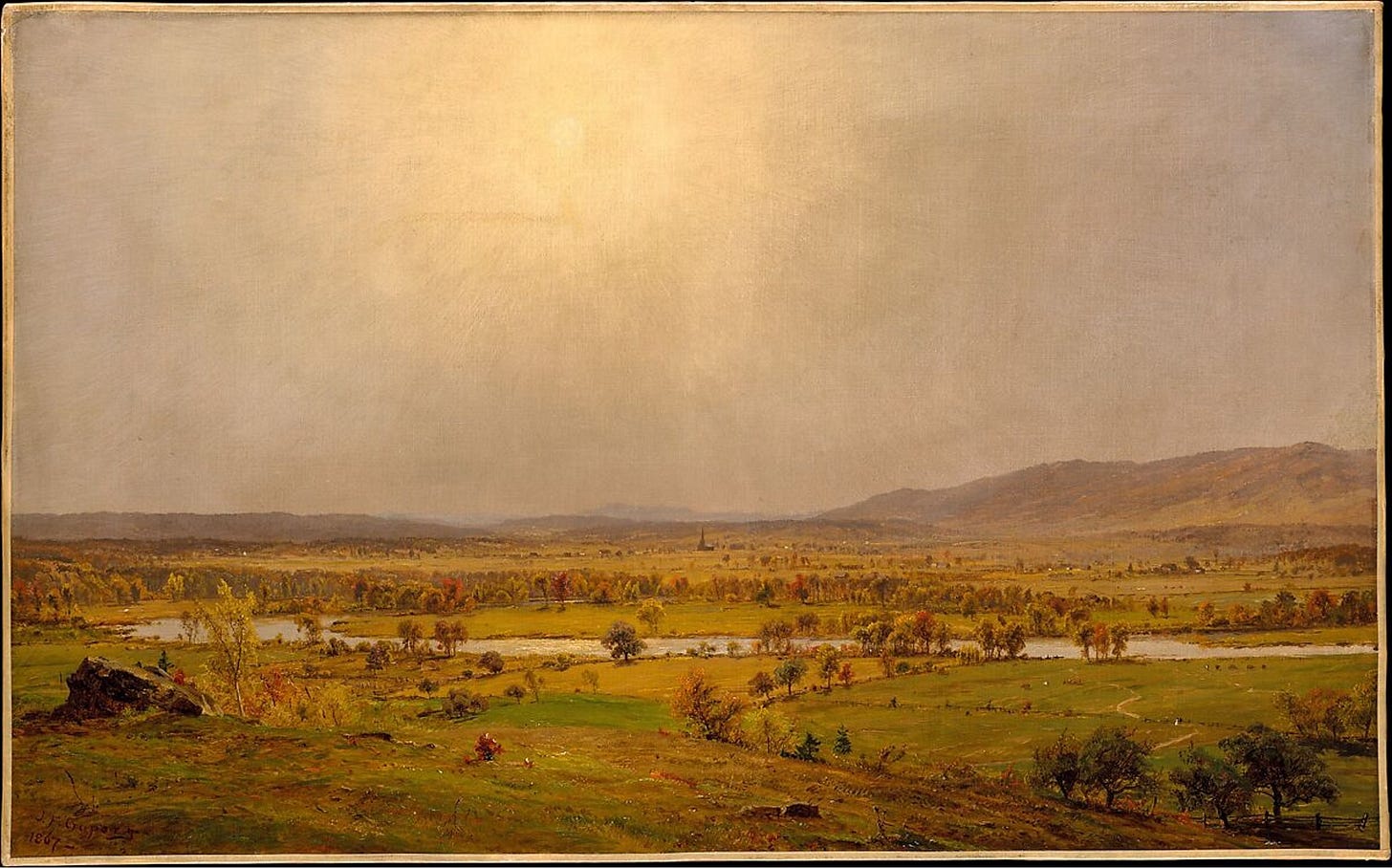

Joining this work brought to bear my work as a historian whose work highlights the intersection of two prominent features in American life in this period, the institution of slavery and the institution of the church. Pequannock was like many communities throughout New Jersey and New York from the colonial period to the rise of the early US republic, with respect to the overlap of these institutions. There, the Dutch Protestant Reformed Church, which became the First Reformed Church of Pompton Plains, was a central site. In fact, the church’s steeple can even be seen in the nineteenth-century painting of the community. But the religious and political landscape of this agrarian community, envisioned by the painter with a romantic idyllic sensibility, was also a site of human bondage.

Slavery was common in New Jersey from the colonial period through the mid-nineteenth century, from the arrival of early Dutch and English investors, settlers, and later colonists. And, it continued all the way until after the Civil War, with some held enslaved all the way up until passage of the 13thAmendment. My esteemed colleague Linda Caldwell-Epps reminded us in this work that unfortunately much of the public still is not aware of the long history of slavery in New Jersey. In this period, many people experienced a spectrum of freedom and unfreedom during their lives, including people of African descent who lived in Pequannock, some of whom were born enslaved and later emancipated themselves or were manumitted, or became indentured servants, sharecroppers, etc.

While unfree forced labor and emergent racial categories were generally the defining feature of enslavement, the history of slavery in New Jersey reveals also that different deathways were experienced in the cultures of early residents. Often, white landowners and churches controlled burial sites to reinforce inequality. In many cases, white pastors and their churches restricted access to services of Christian burial or did not perform the same rites for enslaved or free African Americans in their communities. Many cemeteries were segregated or barred African Americans from being buried near white people. This is true of many church cemeteries of Reformed, Presbyterian, and Congregational churches, the very traditions most directly linked to NBTS in the nineteenth century.

As a result, African Americans often had very few places to conduct burials, had to organize to buy lands where they could honor members of their community, and faced disrespect and disregard of their burial sites. Many were under-documented and unmarked.

As the Paterson Morning Call wrote in 1936 when residents were investigating the disinterment of the burials in Pequannock, “Old residents here recall that slave owners buried their slaves in any handy spot.” In the case of these remains found in Pequannock, one witness reported that several burials of “Negro slaves” were made in the early 1850s at that site. At this location, the DeMotts enslaved dozens of people, many of whom lived and worked at this site, including individuals named York, Dinah, Andrew, Isaac, Amzi, Frank, Jude, Phebe, Manus, Harry, Jack, Charles, Bill, and Mercy. Several other enslaved people whose names were not given in the surviving written records were described in dehumanizing non-personal terms as “negro wench” and “black boy”.

It is outrageous how these ancestors’ remains were mistreated. They lingered forgotten in New Brunswick from 1936 to 2024. The violence they experienced in enslavement and the inequalities of how even their dead bodies were treated was compounded by new violences of being dug up, moved, and disregarded.

But it made all the more meaningful our work to assemble an advisory council that made recommendations about how to rebury these ancestors. We did so with grant funding administered by NBTS from the Luce Foundation-funded Grounded Knowledge Project of the Institute for Diversity & Civic Life. Our group facilitated the work of a collaborative, interdisciplinary group representing diverse individuals and professional backgrounds, including a number of pastors (some of whom were alumni or trustees of NBTS).

This council engaged in this community-centered effort that culminated with the dignified reburial of these ancestors on July 13, 2024 in the cemetary of the First Reformed Church of Pompton Plains.

A critical part of our work was not merely presenting these people as enslaved, but finding ways to document and share the stories of these ancestors, many of whom achieved liberation and made choices about their work, families, and faith. There were several free Black landowners and farmers, including the family of York and Dinah, who had been previously enslaved and became free and purchased land from the DeMotts that they came to own as free people.

Baptismal and Marriage records showed a number of these Black residents of Pequannock attended that church, while enslaved and after obtaining their freedom. Upon our council’s recommendations, their remains were buried in the church cemetery with a dignified service of Christian burial, a place and manner not granted to them in the era in which they lived.

A stone monument was put in place, telling this history and honoring the names of those ancestors, to whom these human remains might have belonged, and who lived, worked, and worshiped in this community.

Also, considering the African diasporic cultural and religious traditions of these and others who were enslaved in New Jersey, our council also hosted a beautiful public meeting in October of 2024 that culminated with reading the names of these ancestors and a ceremony pouring out libation.

Since the reburial and libation ceremony, we have hosted a series of sessions considering that community’s history. We have screened films to educate and inform the local community. We will also continue this work through an exhibit currently under preparation on the life of York and Dinah for the local public library. Additionally, Carol and Rutgers students have developed an online repository of key documents and records pertaining to these ancestors’s lives, and are working with local public school teachers about curricular interventions.

At NBTS, our part of the work continues as an adivsory council members, Dr. elmira Nazombe, will be working out of the seminary with me and other public historians and church leaders on a curriculum for churches to engage in these histories as foundational to any work of repair or racial justice.

Because many enslaved and free African Americans, and the white people who enslaved them, in Pequannock and the surrounding area, were members of the local church, this has required attention and care, and hard work for this church. Returning the bones to this community, saying these names, and reconsidering this history has been a place to gather, a starting point for reckoning with the past.

New Brunswick Theological Seminary and Endowment Funds Derived from Slavery

The community of Pequannock was not unique, and the history of foundational racial injustices supported by Christian religious communities demands our attention and reckoning, too.

The economic advantages enjoyed by Dutch colonists, and then English colonists, in this part of the world, were born of displacement and, often, genocidal intentions toward Native Americans. The wealth amassed by European settlers was then built on the backs of those of African descent. The economic and political power of these colonies-turned-United States was stimulated by enslaved labor and an emergent anti-Indigenous and anti-Black white supremacist social order.

It is not uncommon to praise the history of an institution at a convocation address and we’ve got a long history here in New Brunswick of lauding our founders’ ideals. They did have ideals. The institutions of Queens College and the Theological Seminary founded by the Reformed Church, professed faith in God and theological distinctives that, at their best, sought to bring about God’s reign in the world. But, an idealistic, mythic perspective only tells half of the story, wrongly assuming that prominence and wealth and position were the product of virtue.

Both Rutgers and NBTS have to reckon with the fact that the largest donors to these institutions gave from fortunes directly enriched by slavery. In recent years, Rutgers’s Scarlet and Black Project and the way many of us have embraced the process of reinterpreting our institutional history have raised the profile of what we’ve long known.

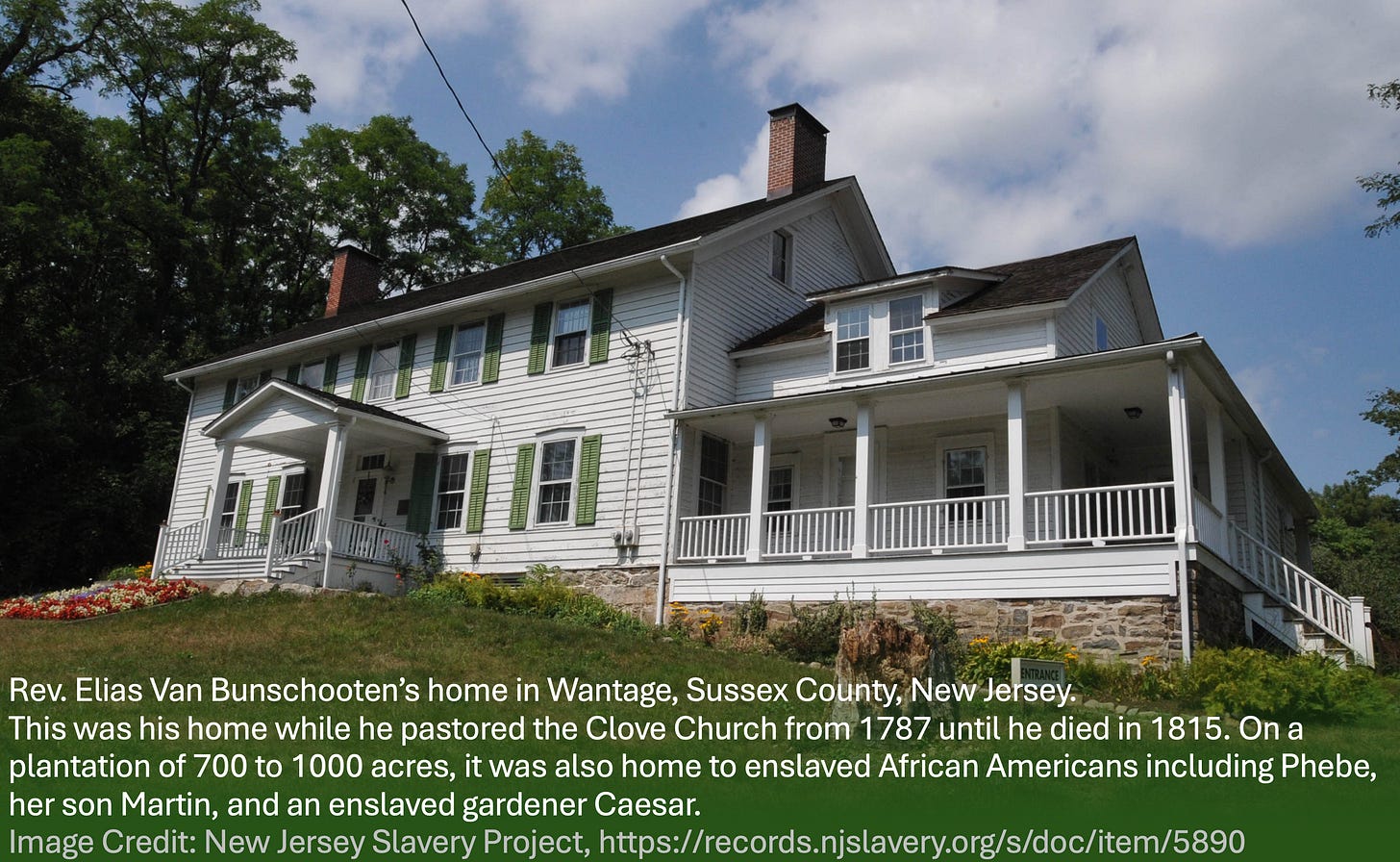

The largest and core endowment gift to NBTS came from the Reformed minister Elias Van Bunschooten and he made sure everyone at the seminary and throughout the Reformed Church knew about it. His total giving in 1814 and at his death in 1815 totaled $17,600, a fortune at the time and more than three times the donation that was made by Colonel Henry Rutgers to the college which was renamed after him. The Van Bunschooten bequest was the product of multiple generations of Dutch and American landholders who enslaved Africans and African Americans, profiting wildly from their labor. And, Elias did not only inherit the money derived from slavery, but also inherited people that his family owned. A county record recently discovered through the research of Dr. Jesse Bayker shows that Elias himself still claimed as enslaved a young boy named Martin who was born after 1804 when the misleadingly-named gradual abolition law in New Jersey supposedly ended the practice of children being born into enslavement. And the same document names the minister’s claim of ownership over Martin’s mother, Phoebe.

Van Bunschooten knew where his fortune was derived. He knew intimately those he and his family claimed as property. His contribution to and acceptance of the institution was shared by our founding professor and president of the Theological Seminary, John Henry Livingston, as well. Livingston had no moral scruples about accepting that bequest, and in fact, he solicited it. Livingston also inherited wealth derived from slavery, with a fortune much larger than Van Bunschooten’s, from his wife’s side of the family that had been enriched by a range of ventures, including use of enslaved labor on New York plantations and funding slave trading between Africa and the Caribbean.

Speaking these institutional histories makes for an uncommon convocation address and is probably even dangerous or forbidden in the present political moment. The present white nationalist authoritarian administration of the United States has condemned teaching that uses terms like racism and slavery, or explores concepts of diversity, equity, and inclusion. Trying to defund higher education, to ban books about these subjects, and to replace history with pro-America myths at the National Museum of African American History and the Smithsonian Institution, they claim that those of us who do history are trying to shame white people. There are some things, in our national past, in our church history, and in the way white supremacy, settler colonialism, and economic exploitation have functioned together in the modern world that are very shameful. Deeply wrong. Sinful. But, confessing sins, and doing history does not bind anyone to shame. Rather, it helps us to understand the past and do the work of liberation.

And of course, these are not the only histories of our institution. We have spent much time telling stories of students, professors, and alumni whose ministry and public life spoke with moral clarity about a witness to justice. This shapes who we are today. New Brunswick Theological Seminary today is deeply ecumenical. We celebrate that the majority of our student body is Black. Our students, faculty, and trustees, represent a range of global cultures and diverse theological traditions – including many Black denominations, such as our siblings in the African Methodist Episcopal Church that from its inception fostered abolition. We carry these histories, too, and honor those ancestors, as well. In so doing we can embrace the work of reckoning. In it, we can find meaning, joy, and hope.

Today, responsive to this moment, we will engage in the Black diaporic practice of Libation. For some of us it is an integral part of our culture and an important practice in our homes and communities. It may be uncommon, unknown to others. But in it, we are invited to name and honor African and African-American ancestors of this place and this institution, whose histories have not been sufficiently reckoned with, including the names of just some of those whose unfree labor became—at the cost of their lives and without their consent—the financial foundation of this school. I would invite those who I’ve identified from our Pequannock public history work to come forward, as in this case, I think the work of members of our extended community needs to inform how we approach the work in this regard that lies before us as an institution. And, I invite you to this libation as a communal act – a practice of doing history, and in some way ancient sacred tradition, responsive to the call to carry the bones of ancestors. In doing so, we are, in a way, gathered to the ancestors, too, and accountable to them. This doesn’t mean the work is complete, but rather we gather and name these ancestors and uncover our hidden histories as a starting point — an opening convocation.